Statistics for Investigating Neuro-aesthetics: a case for Mixed Effects Models

We have investigated several interesting problems in neuro-aesthetics connected to experimental art history. One conundrum in art history is why the figure of Jesus has changed so much: from a curly haired Mediterranean man to the hippie-style Jesus we know today. A second conundrum is why the full front portrait was reserved for portraits of Jesus during most of the renaissance.

A general hypothesis in neuro-aesthetics is that nothing consistent is due to random chance but may be explained by how our perception is structured. Faces are extremely interesting because, as humans, we read so much information from dynamic facial expressions, such as face and gaze direction towards us or others, and we have clear aesthetic preferences for facial symmetry.

It is obvious that symmetry has some connection to health, which is very important for selecting a mate. However, for humans, it does not stop at mate selection. We may also judge trust by self-similarity. However, this may be in conflict with attractiveness that has a component of searching out beneficial genetic variance.

The whole field is complicated by culture, which may present us with a skewed sample of what is culturally attractive and the preferred looks of a trustworthy person. Artists have an interest in surviving from their art, so commissioned portraits will tend to be flattering. However, what is flattering may depend on the message the customer wants to send to the observer.

Paintings of Jesus took off during the Medieval to Renaissance as an image that was aimed for a mass appeal. The image would ideally attract new believers, and the commissioners certainly got feedback on the success of various styles and options. The portraits of Jesus were directed at a general believer and not necessarily a peer. This means that the image should be attractive to both men and women, from all walks of life. It seems to follow the logic that signals of divinity would also need reserved coding. We have suggested that face direction and gaze direction are two important dimensions.

Furthermore, we suggested androgyny, as represented in an image, may be universally more appealing. One reason is recognition of self, as both sexes may see something of self, as well as something of the opposite sex. However, androgyny in a male figure may signal high levels of both youth and health by heightened symmetry in the image.

Galton (1878) created composite images of criminals in order to find features that criminals had in common. He was surprised to find that the composite images became beautiful. The effect was that the random imperfections cancelled out, and the faces became more symmetrical.

It is also clear that the image of Jesus has adapted to the local communities, in interesting ways. In southern Europe, the image tends to have a darker skin tone and brown eyes. The further north in Europe, the paler the complexity and the bluer the eyes. Indeed, it looks like the images have adapted to the local communities in a non-random cline.

Method

How to create controlled images

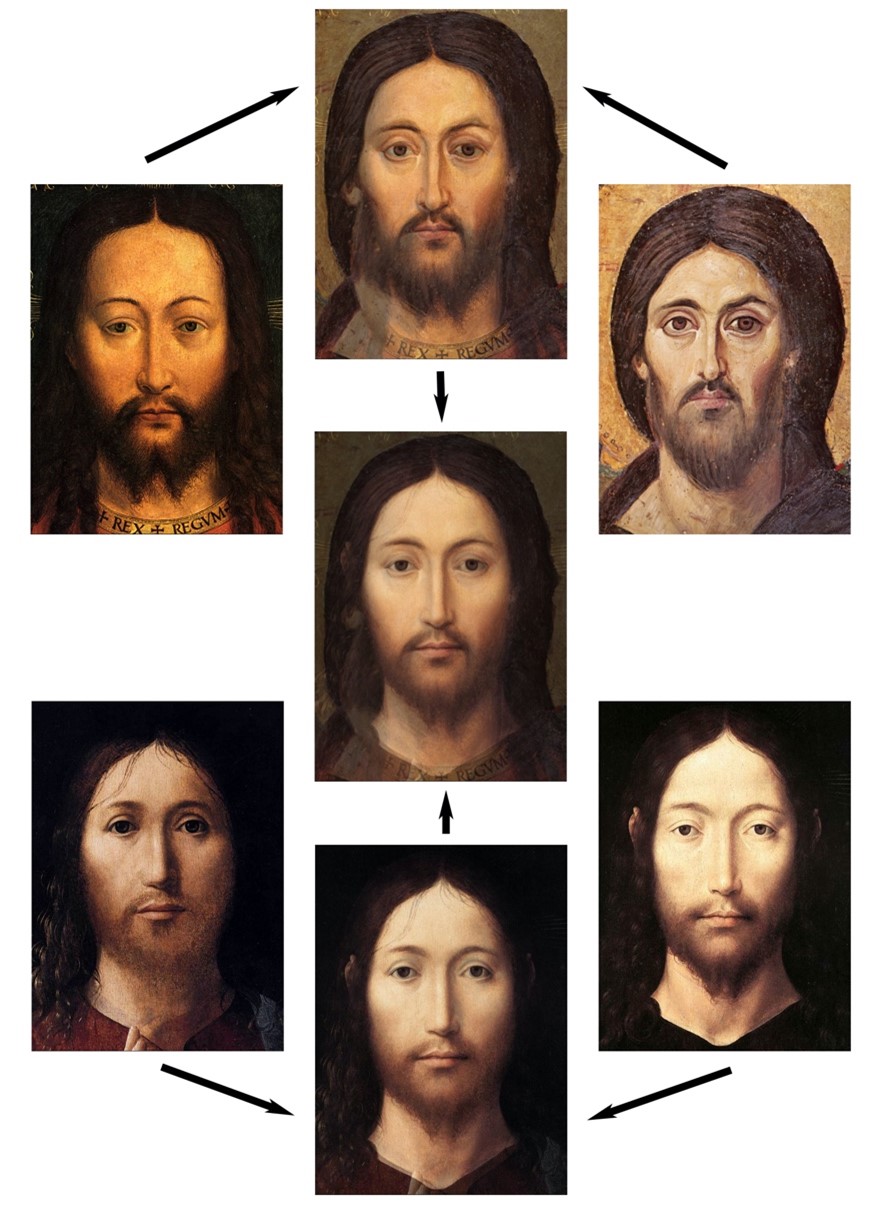

Figure 1 illustrates the procedure of pairwise morphing (averaging) images to form a prototypical portrait consisting of features from many pictures. The algorithm we used assumes pairwise averaging. This means that we are restricted to using a power of two images (2, 4, 8, 16, etc) to reach the final prototype with an equal contribution from all involved images. For the participant prototypes (female, human, male) we used 16, 32, and 16 images (cf. Figure 2). Adding the Jesus prototype results in a feminized, humanized, and masculinized images of Jesus.